IT IS heartening that the euro area has a knack for surviving near-fatal crises. Yet confidence in the durability of the single currency might be stronger if it suffered fewer of them. Europe dodged its latest bullet on May 7th in France, when Emmanuel Macron, a liberal-minded (by local standards) upstart centrist, defeated Marine Le Pen for the presidency. Even so, an avowed nationalist and Eurosceptic captured 34% of the vote, leaving Mr Macron with five years to assuage widespread frustration with the economic status quo. An obvious model lies just across the Rhine, where the unemployment rate—below 4%, down from over 11% in 2005—is testimony to the potential for swift, dramatic change. Yet Germany’s performance will not be easy to duplicate.

It would be unfair to call France the sick man of Europe; half the continent is wheezing or limping. Yet there is certainly room for French improvement. Real output per person has barely risen in the past decade. Government spending stands at 57% of GDP, outstripping the tax take; France’s budget deficit, at 3.4% of GDP, is among the largest in the euro area’s core. The biggest worry, however, is the labour market. The unemployment rate, now 10.1%, is stubbornly high. Nearly a quarter of French young adults are unemployed. Worklessness, especially among young people, is a source of rising social tension and a corrosive force in French politics. Mr Macron must perform the German trick—from labour-market morass to miracle—in half the time it took Germany.

How did the Germans manage it? The popular narrative of the German turnaround begins with the “Hartz reformsâ€â€”named after Peter Hartz, who ran the commission that formulated them—enacted from 2003 to 2005. Germany’s structural unemployment rate had risen steadily from the early 1970s. Each recession added workers to the jobless rolls who subsequently never left. The Hartz reforms overhauled job training and placement programmes and reduced barriers to part-time work. Most important, they transformed a wildly generous system of unemployment and welfare payments, which allowed some workers to collect indefinite benefits equivalent to about half their previous salary, into one which paid fixed amounts for a limited time. The reforms inspired intense opposition and, in 2005, cost Gerhard Schröder the chancellorship (it passed to one Angela Merkel). Yet the pain appears to have been worth it. German leaders are certainly not slow to evangelise about the benefits of reform.

Mr Macron, however, should be careful about mimicking German reforms too slavishly. The groundwork for Germany’s miracle was laid well before the Hartz reforms, in response to unique circumstances. German reunification in 1990 placed great fiscal strain on the economy. And the collapse of Soviet power gave Germany’s eastern neighbours—economies with skilled but low-cost workforces and close historical relationships with Germany—better access to Western markets. Conditions seemed ideal for a swift industrial decline. That prospect spooked German workers into docility. Wage contracts became increasingly localised (helped by the absence of the national wage floors imposed in France) and strike action was rarer than in France or Italy. Union membership dropped; the share of workers covered by industry-level wage agreements fell from 75% in 1995 to 56% in 2008.

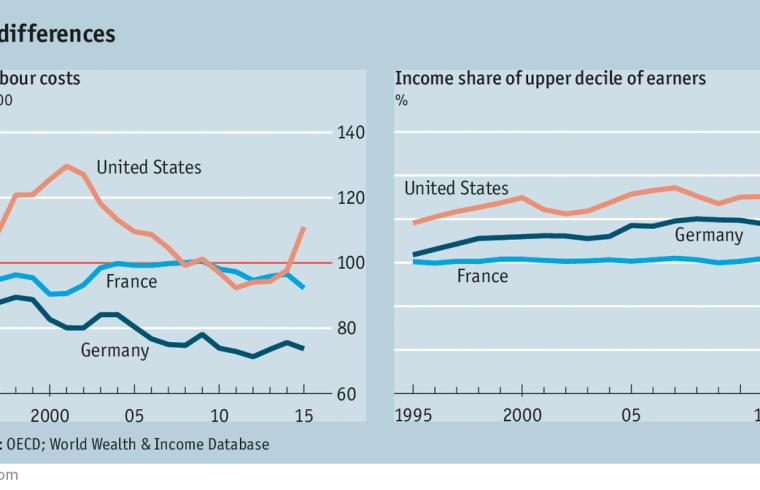

As a result, from the early 1990s labour costs for German firms fell sharply relative to those in other economies (see left-hand chart). Low labour costs reduced the incentive for firms to shift production abroad and boosted the competitiveness of German exports. (Flexibility also shielded the German labour market during the Great Recession, when a sharp fall in GDP barely affected the unemployment rate.) The same political economy that allowed lower German labour costs probably enabled the passage of the Hartz reforms. Yet it made its own, independent contribution to rising German employment.

The Macron environment

Nor can the global context be ignored. In the 2000s the world economy grew at an average annual pace of around 4%, despite the Great Recession. China, which bought much of the industrial equipment manufactured in Germany, grew especially rapidly. Booming global trade amplified the benefits to Germany of rising competitiveness. And German labour costs were falling while those of its European neighbours were flat or rising. Now, the global outlook for output and trade is far murkier. And much of the euro-area periphery is also trying to lower labour costs and boost competitiveness. The Hartz reforms certainly succeeded in pushing some workers back into the labour force and into work; one analysis suggests they reduced Germany’s structural unemployment rate by 1.4 percentage points, for instance. But other shifts in the economy were just as critical to the German turnaround.

Moreover, change in Germany’s labour market was not a story of improvement across the board. Growth in employment soared, but growth in total hours worked did not. To a great extent, Germany redistributed working hours rather than created new ones. Though wages for the better-paid climbed rapidly, especially in manufacturing, they fell for the lowest-paid. So income inequality in Germany, on some measures, has followed a remarkably American trajectory (see right-hand chart). Increased employment in France is a worthy goal; but to make it the sole priority may have unpleasant consequences for some.

The new president seems to understand that danger. Though the details of his programme have yet to be unveiled, they are likely to include reforms to French labour law and efforts to deepen French trade relations with Europe, in addition to more Hartz-like measures. But a successful French turnaround will necessarily look different from Germany’s. If Mr Macron hews too closely to what the Germans believe to have been the secret of their success, France’s disenfranchised may end up feeling even more alienated. If so, the euro zone may suffer another existential crisis, this time possibly terminal.