Sean Strawbridge runs the Port of Corpus Christi in Texas, but he’s been spending a lot of time in Washington lately.

In meetings with White House officials and anyone else who’ll listen, he brings a stack of glossy brochures laying out what he’s after: $ 225 million from the federal government to widen and deepen the channel that ships pass through.

The president’s fiscal 2019 budget for the US Army Corps of Engineers, which owns the channel, requested $ 13 million for the project. Not nearly enough to finish the job, even with the port itself supplying another $ 102 million.

President Trump unveiled a plan in February to turn $ 200 billion in federal money into $ 1.5 trillion for fixing America’s infrastructure by leveraging local and state tax dollars and private investment.

The plan seemed promising, but it hasn’t advanced since. Strawbridge, who hired a brand name public relations firm to help sell his project, is growing less optimistic that the money will be available anytime soon.

“I would say at this point it’s highly unlikely that we’re going to see any legislative tweaks this year,” Strawbridge says. Without substantially more federal funding, the project might have to be delayed or scaled back, making it harder to satisfy the export demand stemming from Texas’ booming oilfields.

“If the federal government for some reason stumbles,” Strawbridge says, “we’re going to have to look at what’s a plan B.”

It’s a tough reality facing local officials from all over the country seeking to get their projects funded. Despite the fanfare surrounding Trump’s 53-page infrastructure plan, the president still needs Congress to draft legislation and appropriate money — and so far there appears to be little momentum to do so.

In response to an inquiry about the status of its program, a White House spokeswoman touted the “down payment” on infrastructure folded into the spending bill that passed last week, including $ 625 million for rural broadband, and a bill backed by the Department of the Interior that would funnel up to $ 18 billion in revenue from energy produced on public lands into upgrades to roads and facilities in national parks.

Related: The biggest infrastructure nightmare facing the United States

But the White House didn’t say when they expect to see a more complete legislative package. A spokesman for the Senate Energy and Commerce Committee, which would draft the bill, declined to confirm a time frame as well.

That’s despite a blitz of lobbying earlier this year from groups like the National Association of Counties and American Society of Civil Engineers.

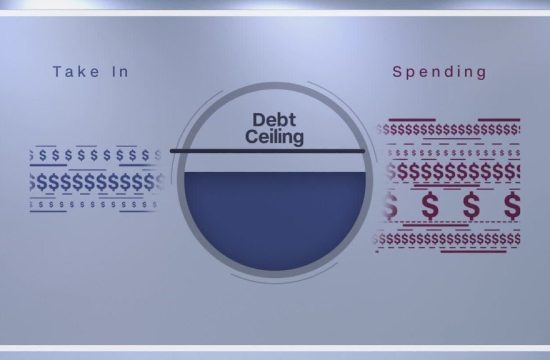

In meetings on Capitol Hill, the petitioners heard a consistent refrainfrom legislators: We know your roads and sewer systems are important, but finding another $ 200 billion for infrastructure after we just ran up the deficit with a $ 1 trillion tax cut is a heavy lift.

“They bet the farm on the tax bill,” said Karen Freeman-Wilson, the mayor of Gary, Indiana, while attending the National League of Cities’ annual legislative summit. “So now, how do you pay for it?”

That’s left local governments wondering where else to turn for the mounting backlog of maintenance projects and improvements that won’t generate enough returns to attract substantial private investment.

Winning federal funding has become more difficult in the absence of earmarks, since members of Congress don’t have much influence over grant-making agencies like the Department of Transportation. Former Florida Representative John Mica, who chaired the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee until 2013, recently told a group of county officials that the best way to win federal funding is to come up with as much money locally as they can.

“The more you can put in the pot, the better chance you get,” Mica advised. “And then lobby like hell, because you’re competing with everybody in this room.”

It’s easier said than done.

Take the city of Arvada, Colorado, which has long sought funds for two major projects: a $ 35 million expansion of an east-west highway since 2001, and an $ 18 million streetscape overhaul to promote pedestrian safety since 2007.

City manager Mark Deven says he’s tried his luck with federal grant programs, like the TIGER grants created by the Obama administration. So far, no luck.

Related: Trump’s infrastructure plan rests on some strong assumptions

“These funds are very competitive,” Deven says. “At a meeting I went to a couple years ago with the federal Department of Transportation, one of the federal officials mentioned that you have a better chance of having your child admitted to Harvard than receiving one of these grants.”

After already taxing their own citizens to pay for improvements, some state and local officials have grown especially frustrated with the lack of federal action.

Michigan, for example, had already raised gas taxes and vehicle registration fees on residents in order to raise funds to repairs its roads and other projects. But in the wake of the Flint water crisis, a commission appointed by the governor found that unmet need for the upkeep of the state’s overall infrastructure was still $ 4 billion per year.

Mark Vanderpool is the city manager of Sterling Heights, Michigan, which is trying to put together $ 217 million for a road that serves the state’s largest manufacturing companies. Along with the county and the city of Warren, he’s applied for enough federal funding to cover 60% of the project, and is crossing his fingers the money comes through.

“There has to be a collaborative effort with infrastructure,” says Vanderpool. “The scope of the problem is so massive. Locals and states are doing what they need to do.”

Although they would welcome any extra funding, as well as the shorter permitting process that the White House also promised in its infrastructure plan, many local officials would rather see a long-term fix to something more basic: The Highway Trust Fund, which is scheduled to run out of money in 2021 as gas tax revenue declines.

Those dollars are parceled out to states on a formula basis, making them more reliable than grants handed out at the discretion of federal bureaucrats.

“The problem we see with how funding has been going overall is on these short-term continuing resolutions,” says Michael Reeves, who runs the Port to Plains coalition, a group that advocates for transportation corridors between Canada and Mexico. “With transportation, it’s a long-term process, and it’s so important to have that long-term certainty.”