It’s a Republican dream come true.

Now that they control both the White House and Congress, Republicans are moving quickly to put their ideological stamp on the nation’s safety net.

Their prime directive: Requiring as many poor adults as possible to earn their benefit check. Making them get jobswill put them on the path to self-sufficiency, while reducing the number of people who depend on public assistance, according to GOP orthodoxy.

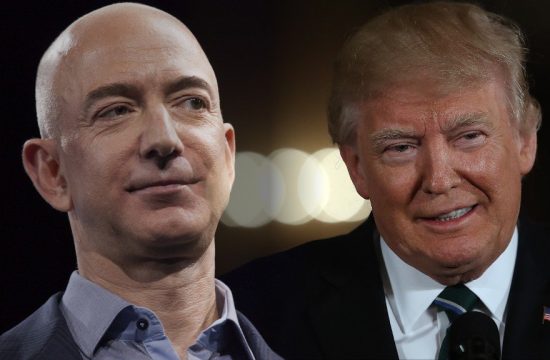

“There’s a dignity to work, and there’s a necessity to work to help the country succeed,” White House Budget Director Mick Mulvaney said last week. “We are no longer going to measure compassion by the number of programs or the number of people on those programs. We’re going to measure compassion and success by the number of people we help get off of those programs and get back in charge of their own lives.”

Currently, work requirements don’t hit many people in the nation’s two largest safety net programs. States can’t mandate Medicaid recipients to work. The food stamp program contains an employment requirement, but it can be — and often is — waived. That will change if Republicans succeed in their overhaul plans.

Related: Safety net is at risk from Trump’s budget ax

In addition to actually having a job, there are a variety of ways recipients could satisfy the work requirement. These include looking for work, attending job training or vocational education classes and participating in community service programs.

The GOP’s efforts, however, have raised an outcry among Democrats and consumer advocates, who call therequirement hard-hearted and misguided. Many poor Americans who can work already do, they argue. Putting in place such mandates doesn’t take into account barriers to employment such as health, child care and transportation. It will only strip benefits from those who need them most, advocates say. Plus, they note, President Trump’s budget proposal strips funding from job training initiatives.

Related: Trump budget proposes 40% cut to job training programs

Here’s how the GOP is seeking to change the nation’s two main safety net programs:

Medicaid: Medicaid is the country’s largest health insurance provider, covering more than 70 million low-income children, adults, elderly and disabled Americans. That includes 11 million low-income adults who gained coverage under Obamacare’s Medicaid expansion provision.

The program doesn’t require enrollees to work, though many do. Nearly 60% of non-disabled, working-age adults have jobs, while nearly 80% live in families with at least one worker, according to a Kaiser Family Foundation analysis.

Several states have asked the federal government to allow them to impose employment mandates, particularly on adults who qualified through Medicaid expansion as a result of Obamacare. The Obama administration rejected any attempts to tie Medicaid benefits to work.

The Trump administration, on the other hand, is encouraging states to apply for waivers to add work requirements, noting it will boost their economic standing and help them gain independence.

“The best way to improve the long-term health of low-income Americans is to empower them with skills and employment,” wrote Health Secretary Tom Price and Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Administrator Seema Verma in a letter to governors in March.

Related: Trump administration open to making some Medicaid recipients work

Republicans in Congress are also on board. The House GOP bill to repeal and replace Obamacare would allow states to impose work requirements on non-disabled, non-elderly, non-pregnant adults. The legislation is currently being debated in the Senate.

Adding work requirements to Medicaid would not severely disrupt the program since so many beneficiaries have jobs or would be exempt, said Ben Gitis, director of labor market policy at the conservative American Action Forum. But, just over one million enrollees would be subject to the mandate, which is still a substantial number, he said.

“It would encourage quite a few people to find work and find their own way out of poverty,” Gitis said.

But it could alsomean folks would lose their benefits, said MaryBeth Musumeci, associate director at Kaiser’s Program on Medicaid and the Uninsured. More than one-third of those without jobs said they aren’t working because of illness or disability, while another 28% said they were taking care of their home or family. Others said they were in school, couldn’t find jobs or were retired.

“Just saying work is required is not enough to get to the end goal,” she said. “It requires more investment of resources and case management.”

Food stamps: More than 40 million Americans receive food stamps — nearly two-thirds of them are children, elderly or disabled. The average household on food stamps had income of less than $ 10,000 a year.

Unlike Medicaid, there is a work requirement on the books in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, the formal name for food stamps.About 44% of food stamp recipients had jobs in fiscal 2015, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which administers the program.

Adults without minor children can only receive benefits for three months out of every 36-month period unless they are working 20 hours a week. But states can waive that requirement for areas with unemployment of at least 10% or an insufficient number of jobs, as defined by the Department of Labor.

Trump’s budget proposal would limit the waivers to areas where unemployment is at least 10%.

Currently, more than one-third of the country lives in areas that are waived from the work requirement, according to the left-leaning Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Under the Trump budget, only 1.3% of the nation would.

Related: Trump wants at least 6 million people off welfare

In discussing the budget last week, Mulvaney suggested there were recipients collecting food stamps who shouldn’t be. Those are the people the administration is looking to put back to work.

“What we’ve done is not to try and remove the safety net for folks who need it, but to try and figure out if there’s folks who don’t need it that need to be back in the workforce,” he said.

But the administration’s suggested work requirement would kick about one million very poor people off the program, said Stacy Dean, the center’s vice president for food assistance policy. Most have low skills, making it tough for them to find a job.

“Taking away food assistance is not going to make looking for work any easier,” she said.