Nearly 107 million Americans have an auto loan.

It’s a record high, and there are growing concerns that many people who obtained their car loans really can’t afford them.

Alarm bells are ringing because one of the largest subprime auto lenders in the nation — Santander Consumer USA — only checked the incomes of 8% of its applicants, according to a new report from Moody’s Investors Service. Subprime refers to loans made to people with poor credit.

“A lack of income verification…creates more uncertainty around whether borrowers will be able to afford their monthly payments,” Moody’s wrote.

By comparison, Santander’s main competitor in the subprime auto lender space — AmeriCredit — verified 64% of applicant incomes.

Santander’s behavior is reminiscent of the practices that led to the home loan crisis where people were getting home mortgages who clearly should not have. The difference is that car loans are for smaller amounts and make up a far tinier portion of the overall economy.

Still, there are concerns since losses at subprime auto lenders are at the highest rate since the aftermath of the Great Recession. S&P Global Ratings found that losses on subprime auto loans in January hit 9.1%, the worst level since 2010.

“The warning bells are blaring too loud to ignore any longer,” says Erin Mahoney of the Committee for Better Banks, a group advocating for reform.

Related: Auto sales are slowing, and upheaval is next

Santander is pushing back by saying that it looks at many metrics to determine if someone should get a loan. Proof of income isn’t always the best indicator of whether someone can repay a loan, some say.

“We are entirely committed to treating our customers fairly and lending responsibly,” a Santander Consumer USA spokeswoman told CNNMoney. “We consider a wide range of factors to manage and price for risk.”

Related: A record 107 million Americans have car loans

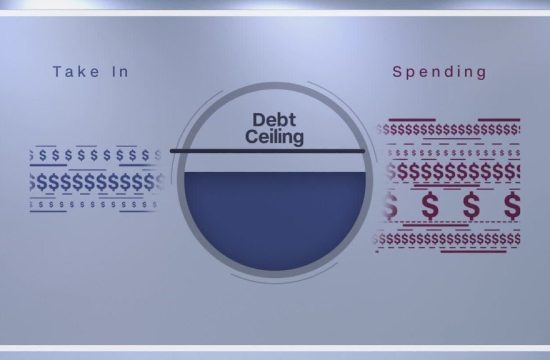

Moody’s points out that this doesn’t mean it’s time to panic. The auto loan industry is much smaller than the home loan market. Even if a lot of people do default on their car loans, it wouldn’t rock the global economy in the same way the mortgage crisis did.

“The size is not comparable,” says Nicky Dang, a vice president at Moody’s.

People don’t need to take out nearly as much debt to buy a vehicle. While the typical American home costs around $ 200,000, the average new car is about one-sixth that amount, or under $ 35,000.

Dang also says that while auto loan defaults have risen recently, they are “definitely not that high” compared to historical trends.

The other key difference is that nearly all home mortgages were being packaged together on Wall Street and sold on to investors globally on a mass scale. That’s not happening at nearly the same extent with auto loans. Less than 20% of subprime autoloans are “securitized” on Wall Street, according to S&P Global.

In its report, Moody’s was looking specifically at income verification of car loans that were packaged together into bonds.