In 2007, Apple unveiled the iPhone.

Apple didn’t invent the smartphone — companies like Palm and Blackberry had been selling them for years. But the iPhone introduced a totally new way to interact with computers. The always-on internet connectivity, finger-friendly touch screen, and interface based around clickable app icons all seem commonplace now. But at the time, the whole package felt revolutionary.

The smartphone was a seismic shift for the technology industry, creating entirely new business models — apps became $ 100 billion companies — while replacing everything from digital cameras to in-car GPS systems.

But smartphone sales have dropped two calendar years straight for the first time, according to Gartner. Smartphones are old news.

The tech industry’s next bet is a series of technologies usually called augmented reality (AR) or mixed reality. The vision usually involves some kind of computer worn in front of the user’s eyes.

Users will still be able to see most of the real world in front of them — unlike virtual reality, which completely immerses the user in a computer-generated fantasyland, augmented reality layers computer-generated text and images on top of reality.

Industry watchers and participants think that Apple has a good chance to validated and revolutionize AR like it did with smartphones. Apple has been prototyping headsets for years, and recent reports from The Information and Bloomberg suggest that Apple could release a headset as early as 2022 that could cost as much as $ 3,0000.

But Apple’s not the only company working on these products. All the big tech players — Microsoft, Google, Facebook, and Amazon — are in the game as well.

Futurists and screenwriters have conjured blue-sky visions of what could happen with advanced computer glasses — one episode of the dystopian anthology “Black Mirror” explored a world where people could “block” certain people out of their view. More positive visions imagine having important information coming directly into your view, exactly when you want it.

Today, the most common use cases are much more mundane, including smartphone-based games and apps like Pokemon Go or Apple’s Ruler app, which use the phone’s screen and camera rather than relying on glasses or another set of screens sitting on your face. The few companies who are actively producing AR glasses are mostly focused on work scenarios, like manufacturing and medicine.

“That’s where we now sit in spatial computing’s lifecycle. It’s not the revolutionary platform shift touted circa-2016,” said Mike Boland, technology analyst and founder of ARtillery Intelligence, in a recent report. “It’s not a silver bullet for everything we do in life and work as once hyped. But it will be transformative in narrower ways, and within a targeted set of use cases and verticals.”

Here’s what the biggest companies in tech are doing to try and make augmented reality the next big thing:

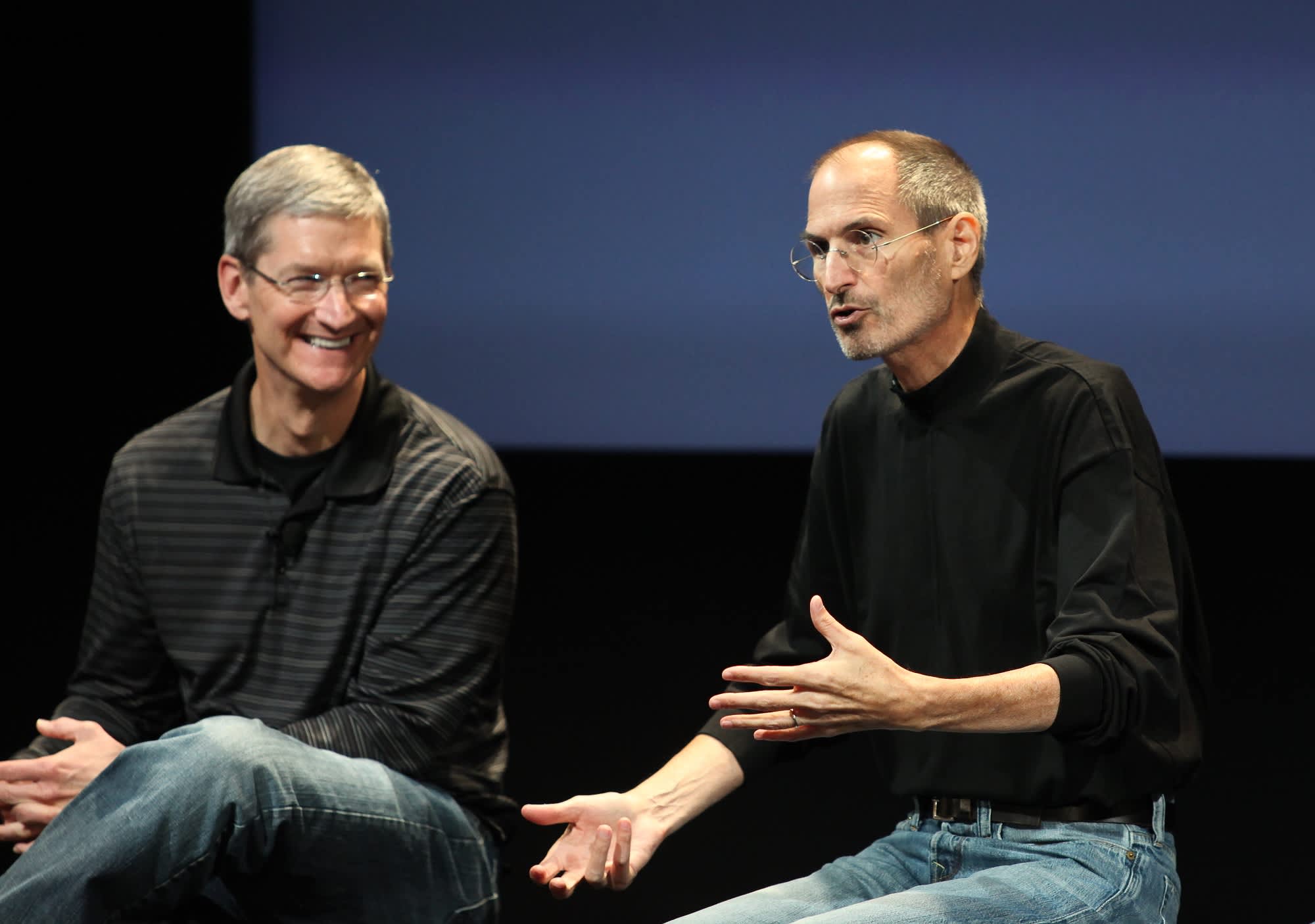

Apple

Apple’s generation-defining success with the iPhone has made it the company to watch in augmented reality — even though the company has never confirmed it is working on a headset, glasses or any other kind of head-worn computer.

Boland says that if Apple were to release a pair of AR glasses, it could “determine the fate of the AR industry,” given the company’s track record of popularizing new technologies.

A report from Bloomberg last month suggested Apple’s first AR product could be out as early as next year. Its first shot will reportedly a battery-powered headset that’s primarily designed for virtual reality, but with on-board cameras to enable augmented reality as well. The report says this device could cost thousands of dollars and be available only in low volumes — more typical of a test platform for software developers than the mass-market products Apple usually releases.

Eventually Apple could take lessons it learns from the virtual reality headset and apply it to a pair of lightweight AR glasses with transparent displays. But according to Bloomberg, that project still faces additional work on technical issues such as miniaturization and lens technology.

Display technology is another limiting factors for augmented reality. The transparent displays currently on the market have a limited field of view in which they can display graphics, are often not bright enough for daylight use, and generally could be better suited for all-day wear.

Apple’s working on solving this problem, too, according to a report in Nikkei Asia. The newspaper says that Apple is working with TSMC, its primary processor manufacturer, to develop a new kind of augmented reality display that’s printed directly on wafers, or the base layer for chips.

If Apple does eventually reveal a big leap forward in AR display technology — especially if the technology is developed and owned by Apple instead of a supplier — Apple could find itself with multi-year head-start in augmented reality as it did when the iPhone vaulted it to the head of the smartphone industry.

Of course, that’s assuming that there’s software worth using when the headset comes out. But Apple has already laid the groundwork for a rich software library.

In 2017, Apple released software called ARKit, which includes tools for software makers to determine how far away an object or wall is, if the phone is moving, or identify limbs in a human body, among other functions.

Companies like Ikea, Target, and Amazon have already used ARKit, mostly for placing virtual furniture in a room to see if it fits. Warby Parker uses it to enable virtual glasses try-ons through its app. Snap uses new iPhone 3D sensors to improve its face-shifting lenses, which advertisers can purchase. But so far, few ARKit apps have found a wider audience.

Apple is also adding hardware to its iPhones that hint at a headset-based future. High-end iPhones released in 2020 include advanced Lidar sensors embedded in their camera. These sensors can measure how far away objects are, and are currently used to execute fun filters and photo effects. But when paired with an advanced headset, their use could be more profound. Apple is considering using lidar sensors on its headset, according to The Information.

One way to look at Apple’s investment in the technology is to look at the companies it’s bought in the field. It’s bought a company that builds transparent optics, a headset maker, and companies that make software and content for augmented and virtual reality, including Akonia Holographics, Vrvana, Metaio, Emotient, Flyby Media, Spaces, and NextVR.

Google was the first major technology company to release a head-worn computer when it introduced Google Glass in 2013. It cost $ 1,500 at the time, and was explicitly targeted at people in the computer industry and early adopters, which Google called “explorers.”

Google’s approach was significantly lighter and simpler than what’s come since. Google Glass did not attempt to use advanced processing to integrate computer graphics into the real world. Instead, it was equipped with a camera, and had a little transparent display with relatively low resolution on the right temple. That display was used to project small bits of information into the user’s field of vision — sort of like an Apple Watch or smartwatch on the user’s face.

But Google Glass was also a lightning rod for criticism — it had a built-in video camera, and people who weren’t wearing it felt like they were being watched. One wearer said she was assaulted outside a San Francisco bar in 2014 for wearing the glasses.

Google paused Glass in 2015 and rejiggered it for business users. Last year, it started selling Google Glass for $ 999 per unit through some of its hardware resellers.

One key application for Glass is Augmedix, which uses the headset’s camera to cut down on the time doctors spend on busywork. The Glass camera streams an interaction with patients to “scribes” hired by the company who write down the important details and enter them into the patient record.

Last year, Google acquired North, a Canadian company making a pair of lightweight $ 1,000 smartglasses.

Microsoft

Microsoft announced its augmented reality headset, Hololens, in 2015, and released the first version in 2016. It’s now on its second version, which costs $ 3,500. It’s a niche device targeted for business sales. (Microsoft’s tagline: “Work smarter with mixed reality.”)

On its website, Microsoft touts manufacturing, retail, and healthcare as primary use cases. In factories, the headset can inform workers about how to fix or operate a complicated machine. Retailers, instead of having costly display items or large amounts of inventory, can virtually display their goods to customers, Microsoft suggests.

Microsoft’s store currently has 343 HoloLens apps. None are household names, and many are simple demos that display graphics like a birthday cake or fireworks.

Microsoft has invested heavily in these kind of technologies, purchasing AltspaceVR, a social network for virtual reality, in 2018. Before it launched Hololens, it paid $ 150 million for intellectual property from a smartglasses pioneer. It doesn’t break out Hololens sales or revenue.

Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg speaks the most in public about his hopes for augmented reality. Last year, he said, “While I expect phones to still be our primary devices through most of this decade, at some point in the 2020s, we will get breakthrough augmented reality glasses that will redefine our relationship with technology.”

Facebook’s enthusiasm for augmented reality is driven in part by its dependence on smartphone platforms from other vendors today. In particular, Facebook has been balking at Apple’s control over the iPhone for years, and the fight has escalated recently as Apple is planning technical changes to the iPhone software that will hurt Facebook’s main moneymaker, mobile advertising.

If Facebook creates the next big platform, then it will set the rules.

Zuckerberg is also predicting massive societal change stemming from augmented reality: “Imagine if you could live anywhere you chose and access any job anywhere else.”

Facebook is already a leader in virtual reality, augmented reality’s cousin. It bought Oculus for $ 2 billion in 2014, a move that signaled the start of massive investment in these technologies. The latest Oculus headset includes cameras, costs $ 300, and sold 1 million units in December, according to an estimate from SuperData.

With cameras mounted on the front and powerful processing, virtual reality headsets can approximate augmented reality by displaying a real-time feed of the outside world. This feature is called “passthrough” on recent Oculus headsets, and it could be Apple’s initial approach as well.

The company is also working on lightweight AR glasses and hopes to launch a product this year in partnership with Luxottica, the sunglasses giant, CNBC previously reported.

Facebook is also working on “Project Aria,” which is a research-oriented pair of computer glasses that don’t have advanced AR displays, but can record video, audio, track the user’s eyes, and access location data.

Amazon

Amazon is the tech giant with the least public enthusiasm about augmented reality technology, but it does sell a pair of smart glasses called Echo Frames. These don’t even have a display. Instead, the user interacts entirely through Alexa, Amazon’s voice assistant.

Amazon is also attacking augmented reality different angles. Last fall it released an “Amazon Augmented Reality” app, but it’s not a serious piece of software. Instead, it uses QR codes on Amazon shipping boxes to activate fun mini-games, like turning an Amazon box into a race car, or putting fun sunglasses on a dog.

“Augmented reality is a fun way to reuse your Amazon boxes until you’re ready to drop them in the recycling bin,” according to the app’s description.

Other Amazon applications use augmented reality to place virtual furniture inside the user’s home to make sure it fits before making an online purchase.

But Amazon has many of the pieces to take augmented reality more seriously. It has expertise in computer vision, or the software that can identify what objects in a photo or video are. It has an industry-leading voice assistant that could be deeply integrated with the headset.

Amazon also has hundreds of thousands of warehouse workers that could be early adopters of AR glasses — one commonly pitched use case is to help “pickers” find items in a large warehouse more easily by highlighting them with computer graphics.