ANTAGONISM is built into the nature of sexual reproduction itself. Members of each sex try to maximise their own reproductive fitness, which is a combination of the quality and the quantity of offspring they are able to raise to the point where those offspring can themselves reproduce. If conflict between males and females is part and parcel of reproduction, some still have it much tougher than others. Spare a thought, in particular, for the females of the cowpea seed beetle.

Males of this species have penises armed with sharp spikes. These can do serious damage to a female’s reproductive tract. And all in the name of male procreative success, for previous research has shown (though the precise mechanism remains obscure) that male cowpea seed beetles with longer penile spines have greater mating success than those with short ones.

Evolutionary theory predicts that it would be in the interests of females to fight back, by evolving countermeasures. And they seem to have done so, by evolving thicker tract sheaths. But the details have not been studied until now. That has just been corrected by Liam Dougherty of the University of Western Australia and his colleagues. Their paper, published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society, looked at 13 populations of cowpea seed beetles from around the world and showed how reproductive-tract-thickness and two other defensive measures varied with the size of the local males’ armaments. It also showed that the cowpea seed beetle’s spiked penises, and the females’ responses to them (or, rather, the stretches of DNA that underlie these phenomena), are an excellent example of what Richard Dawkins, an evolutionary biologist, called “selfish genesâ€. For while such traits are good for the individual beetles that carry them, they appear to be bad for the health of the species as a whole.

Cowpea seed beetles are widely studied animals because they are important pests of stored pulses. They are found on every continent except Antarctica (Dr Dougherty’s experimental subjects were derived from Africa, Asia and North and South America), and are believed to have been spread around the world from their west African home by human travellers and traders. Hence, any differences between local populations must be the result of recent evolution.

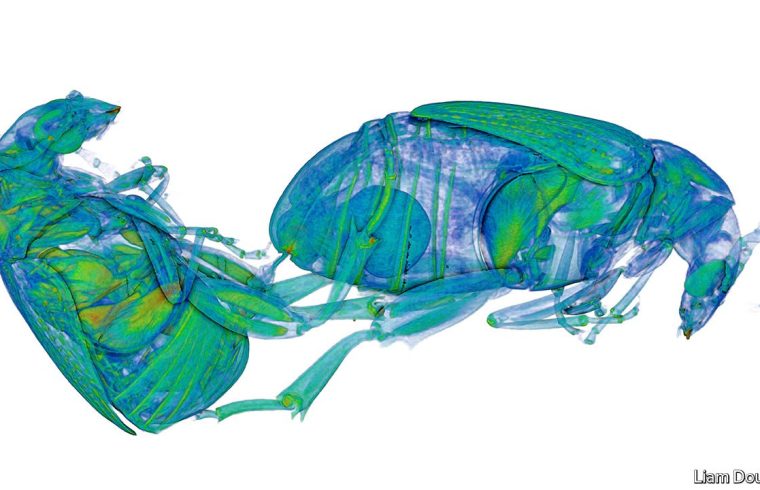

Dr Dougherty and his colleagues first used a technique called micro-CT X-ray scanning, a miniaturised version of medical body-scanning, to measure the thickness of the reproductive tracts of females from each of the populations under study. They also measured the levels in a beetle’s haemolymph (a fluid that performs in insects a similar function to that performed in mammals by blood) of an enzyme called phenoloxidase, which helps repair wounds. And, as a third measure of self-protection, they measured female haemolymph’s microbicidal potency by watching its effect on bacteria in a Petri dish.

For the males, the team measured the length of both the ventral and the dorsal spikes of the penis, and also the amount of damage, measured as scar tissue a day after intercourse, that males of a particular population inflicted on the reproductive tracts of females. (They used this as a proxy for the forcefulness of a male’s advances.) They then looked for correlations between male offensive measures and female defensive ones.

They attacked the data with two different statistical techniques, looking for correlations between the males’ characteristics and the female ones. Both types of statistics indicated that the correlations were strong. Only in the case of ventral penile spines did they fail to suggest that it was the size of the male traits which was responsible for driving the evolution of the size of the female ones.

On top of all this, Dr Dougherty and his team also found that the populations with the most highly developed female defences were those that had shown the lowest population-growth rates in a previous experiment. Since the beetles had been supplied with abundant food, the presumption had been that the growth rates then observed were governed by female fecundity. In light of the latest results, that suggests females in those populations were diverting scarce physiological resources from producing eggs to defending themselves against male sexual aggression—and thus slowing the growth of the population as a whole.