When the condor came, I was seated in a plastic chair, soaking high-altitude sun rays after more than a week of rain and cold.

The bird circled a few times far above my head, and then flew away toward the green and brown mountains that surround the village of Cabanaconde, Peru. The locals believe that when a condor flies overhead, somebody is about to die. But for me, the sight of the condor — regal, peaceful — suggested something different: A message, maybe, from my parents, both of whom I had just lost, half a world away, to COVID-19.

I’m a professional travel writer, and I was on assignment working on a guidebook in Peru when the coronavirus epidemic swept the globe. As I write, I remain stuck abroad — at a place called Mirko’s Home Backpacker, in Cabanaconde, at the mouth of the Colca Canyon, north of Arequipa — unable to travel back to Italy, where I’m from, or home to Malaysia, where I live. On March 16, Peru’s president, Martin Vizcarra, ordered a complete lockdown. When my parents became ill, there was no way to reach them.

“I love you, baby. I can’t talk much anymore; this flu is really knocking me down,†my mom, Tundra Sartorel, told me over the phone from Italy, the last time we spoke. “Please… always stay safe, and don’t come back now.â€

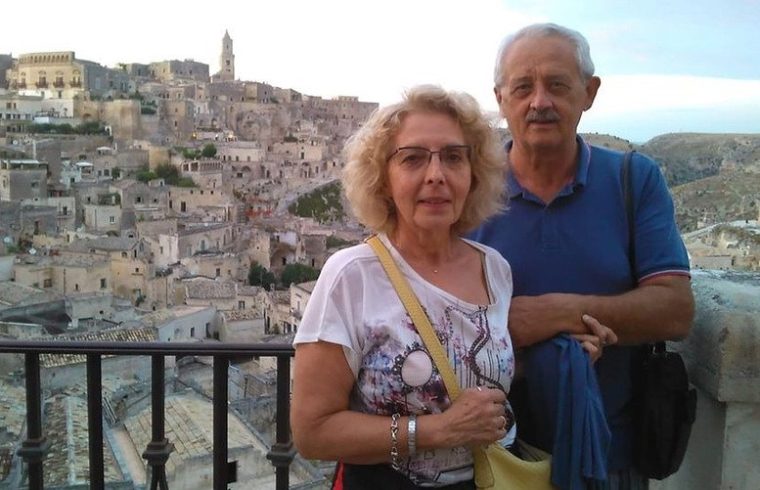

My mom lived a fulfilling but ordinary life in Voghera, a small town in Lombardy. Originally from Milan, she had met my father, Maurizio Ferrarese, at her first office job. When they married a few years later, they decided to move to my father’s hometown — something she would always kind of regret later in life. Tundra was kind and cheerful to anybody, naturally curious, and a real fish out of water in Voghera’s very provincial aquarium. She took care of all the small details to make everyone who visited our home feel very much appreciated, cared for, and welcome.

I last saw her at the departure hall of Malpensa Airport in November 2019, a month before the novel coronavirus that took my parents first appeared in China. My parents were concerned about my trip. With Chile on fire with protests, Bolivia’s president ousted and exiled and Argentina about to have new elections that would have changed its political orientation, my father made some good points. “Latin America is very dangerous right now,†Maurizio said.

But to me, there was no place else I wanted to go. My father and I had completely different priorities in life, and it caused tension between us. While my mom and I could happily dress up the Christmas tree listening to Roky Erickson’s “Two Headed Dog†together, I couldn’t sit in a room with dad for 10 minutes without starting an argument.

And yet, beyond fighting, we were both enamored with each other. He would always be there, seated in an airport lounge chair, a tad older and wearier each and every time I came off a plane from Asia.

Maurizio didn’t like to say it openly to me, but he was very proud of how I managed to build a life for myself in a faraway country. All his friends and colleagues knew about me. Meanwhile, I respected the way Dad had managed to carve his own life path, supporting a family doing what he loved — a very valuable life skill he passed onto myself and my brother, Diego.

Dad was 71 and was waiting for a hip replacement right before the COVID-19 distancing protocols started to be taken seriously in Italy. “We need to go see a doctor in Alessandria tomorrow… who knows if we’ll ever get over this,†Mom, who was 68, whispered in my phone’s earpiece as I glanced at the city of Cusco spreading quietly across a mountain valley in the pristine morning light. The surgery was scheduled for March 9, just when I would have returned from hiking to the ruins of Choquequirao, Machu Picchu’s lesser-known sister.

I called Mom for the last time on March 14 from the village of Yangde, where I was checking properties in the Colca Canyon region of Southern Peru. It was the day before the Peruvian president announced a full lockdown — and the same day my parents left our home to enter Voghera’s hospital ward. “We keep having a high fever, but the doctor came and said it’s just the seasonal flu,†my mom told me. They had, of course, been misdiagnosed. Dad was so wrecked in bed he didn’t even want to say hello on the phone.

In our last days on earth as a family, we were all trapped — me, in the 3,300-meter-high mountain village I chose for isolation, and them in a provincial hospital ward near Lombardy’s hecatomb. “They are stable,†said Diego, a biologist bound by the interprovincial lockdown in Piacenza, 45 miles away from them — as powerless as me, thousands of miles away in Peru.

On March 20, I broke my confinement and ran down to the local police station to ask for help getting home. My mother was getting worse. The cops sent me back to my hostel; without an embassy letter and a confirmed flight, there was nothing I could do.

Tundra died a few hours later. The umpteenth phone call over shaky internet connection ripped my soul apart. The blue check marks in our WhatsApp feed showed me that my mom had read my final words of love.

More: Stories of the lives lost to COVID-19

Dad carried a phone with him — me and my brother were terrified that someone would tell him about our mother’s death. I spent three days advising people to refrain until he could get out of the ward. But on the morning of March 23, when I switched on my phone and saw that my brother had called 15 times since 2 a.m., I knew that Dad had already rejoined his beloved wife.

“We are alone,†Diego said.

I heard him cry for the first time in a dozen years, and I realized that I had just become a 39-year-old orphan.