THE abrupt departure of Ford’s boss, Mark Fields, which the firm announced on May 22nd, has two explanations. Investors had become restive at its performance, particularly in the past year. But Mr Fields was also perceived to lack the drive of Alan Mulally, the man he succeeded. In replacing him with Jim Hackett (pictured), who ran an office-furniture company before joining Ford’s board in 2013 and more recently led the firm’s mobility unit, Ford hopes to conquer current problems and shore up its future strategy.

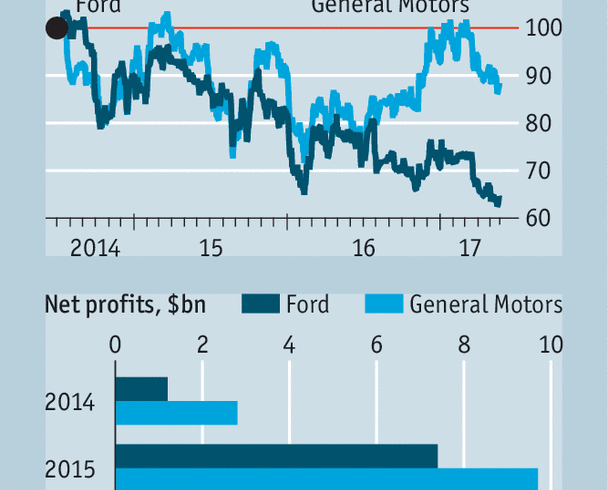

Ford’s shares have declined by nearly 40% since Mr Fields took over (see chart). Though it made record profits in 2015 and had strong results in 2016, investors reckoned a booming North American market, on which it relies for nearly two-thirds of revenues, would slow. They also disliked the fact that Mr Fields had to invest heavily in new technologies. Ford suffered the ignominy of its market capitalisation being surpassed by Tesla, a maker of electric cars which turns out a fraction of the 6.6m vehicles that roll off Ford production lines each year. Being slammed for running a declining firm and for hurting profits by investing in the future was a no-win situation.

Despite his relative lack of experience in the carmaking business, Ford presented Mr Hackett as the “transformational leader†to “re-energise†the firm. After running Ford Smart Mobility, a unit overseeing driverless cars and other new technologies, Mr Hackett may combine an insider’s feel and, like Mr Mulally, an outsider’s ability to challenge the status quo. He promises to speed decision-making, cut bureaucracy and, less convincingly, to add a dose of “fun†at Ford.

Adjustment is required across the industry. Selling services will present a huge challenge to firms hitherto geared to selling cars. New competition from tech firms such as Google, Apple and Tesla has instilled a sense of panic among all carmakers as they grapple with new technology.

Nonetheless, Ford is under pressure to catch up with its rivals and to communicate better. GM recently launched the Bolt, a cheapish electric car, and has been commended for far-sighted investments in Lyft, a ride-hailing service, and Cruise Automation, a self-driving startup. Ford’s plans for electrification are far less advanced, and a recent investment of $ 1bn in Argo, another self-driving startup, was criticised as too pricey. Mr Hackett will leave the job of managing external relations to the smooth-talking Bill Ford, the company’s chairman and a member of the family that still controls the carmaker.

As well as casting an eye to the future, Mr Hackett will have to face Ford’s present ills. There is not much he can do about its lack of scale compared with the industry’s big hitters. Few carmakers are ready to risk the big mergers that would address the industry’s overcapacity. Nor can he do much to improve a brand that lacks cachet. Ford’s foreign operations have weak returns. GM has been more aggressive: selling its European operations and shutting down in India and South Africa. To tackle overcapacity Ford recently said it would cut its global salaried workforce by a tenth, but that may not be enough to stem losses in India and other emerging markets. A dependence on America will prove troublesome, as the market seems to have peaked.

Another task will be to set up a successor to steer the company in a few years’ time, when new technologies will have become an even more important part of Ford’s business. Jim Farley, Ford’s European boss, and Joe Hinrichs, in charge of the Americas, will take more senior roles, both in Detroit, to be groomed. If Mr Hackett can ensure that the next change at the top occurs at a more measured pace, that will be something.